More on Modules and their Namespaces

Suppose you've got a module "binky.py" which contains a "def foo()". The fully qualified name of that foo function is "binky.foo". In this way, various Python modules can name their functions and variables whatever they want, and the variable names won't conflict — module1.foo is different from module2.foo. In the Python vocabulary, we'd say that binky, module1, and module2 each have their own "namespaces," which as you can guess are variable name-to-object bindings.

For example, we have the standard "sys" module that contains some standard system facilities, like the argv list, and exit() function. With the statement "import sys" you can then access the definitions in the sys module

and make them available by their fully-qualified name, e.g. sys.exit(). (Yes, 'sys' has a namespace too!)

import sys

# Now can refer to sys.xxx facilities

sys.exit(0)There is another import form that looks like this: "from sys import argv, exit". That makes argv and exit() available by their short names; however, we recommend the original form with the fully-qualified names because it's a lot easier to determine where a function or attribute came from.

import sys

# Now can refer to sys.xxx facilities

sys.exit(0)

Online help, help(), and dir()

dir(sys)—dir()is likehelp()but just gives a quick list of its defined symbols, or "attributes"

The "print" operator prints out one or more python items followed by a newline (leave a trailing comma at the end of the items to inhibit the newline).

A "raw" string literal is prefixed by an 'r' and passes all the chars through without special treatment of backslashes, so r'x

x' evaluates to

the length-4 string 'x

x'. A 'u' prefix allows you to write a unicode string literal (Python has lots of other unicode support features -- see

the docs below).

raw = r'this

and that'

print raw ## this

and that

multi = """It was the best of times.

It was the worst of times."""String Methods

Here are some of the most common string methods:

- s.lower(), s.upper() -- returns the lowercase or uppercase version of the string

- s.strip() -- returns a string with whitespace removed from the start and end

- s.isalpha()/s.isdigit()/s.isspace()... -- tests if all the string chars are in the various character classes "s.isalpha()"discriminate the string s whether contains only alphas. example:1. s='dfd24s',s.isalpha() returns false; 2. s='sdufjd',s.isalpha() returns Ture.

- s.startswith('other'), s.endswith('other') -- tests if the string starts or ends with the given other string

- s.find('other') -- searches for the given other string (not a regular expression) within s, and returns the first index where it begins or -1 if not found

- s.replace('old', 'new') -- returns a string where all occurrences of 'old' have been replaced by 'new'

- s.split('delim') -- returns a list of substrings separated by the given delimiter. The delimiter is not a regular expression, it's just text. 'aaa,bbb,ccc'.split(',') -> ['aaa', 'bbb', 'ccc']. As a convenient special case s.split() (with no arguments) splits on all whitespace chars.

- s.join(list) -- opposite of split(), joins the elements in the given list together using the string as the delimiter. e.g. '---'.join(['aaa', 'bbb', 'ccc']) -> aaa---bbb---ccc

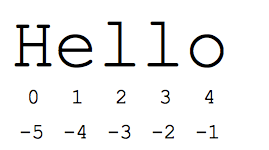

String Slices

- s[1:4] is 'ell' -- chars starting at index 1 and extending up to but not including index 4

- s[1:] is 'ello' -- omitting either index defaults to the start or end of the string

- s[:] is 'Hello' -- omitting both always gives us a copy of the whole thing (this is the pythonic way to copy a sequence like a string or list)

- s[1:100] is 'ello' -- an index that is too big is truncated down to the string length

String %

Python has a printf()-like facility to put together a string. The % operator takes a printf-type format string on the left (%d int, %s string, %f/%g floating point), and the matching values in a tuple on the right (a tuple is made of values separated by commas, typically grouped inside parentheses):

# % operator

text = "%d little pigs come out or I'll %s and %s and %s" % (3, 'huff', 'puff', 'blow down')# add parens to make the long-line work:

text = ("%d little pigs come out or I'll %s and %s and %s" %

(3, 'huff', 'puff', 'blow down'))在python中是没有&&及||这两个运算符的,取而代之的是英文and和or

reference:

https://developers.google.com/edu/python/