Item 61: Don’t Block the Event Queue on I/O

JavaScript programs are structured around events: inputs that may

come in simultaneously from a variety of external sources, such as

interactions from a user (clicking a mouse button, pressing a key, or

touching a screen), incoming network data, or scheduled alarms. In

some languages, it’s customary to write code that waits for a particu-

lar input:

var text = downloadSync("http://example.com/file.txt"); console.log(text);

(The console.log API is a common utility in JavaScript platforms for

printing out debugging information to a developer console.) Func-

tions such as downloadSync are known as synchronous, or blocking:

The program stops doing any work while it waits for its input—in this

case, the result of downloading a file over the internet. Since the com-

puter could be doing other useful work while it waits for the download

to complete, such languages typically provide the programmer with

a way to create multiple threads: subcomputations that are executed

concurrently, allowing one portion of the program to stop and wait

for (“block on”) a slow input while another portion of the program can

carry on usefully doing independent work.

In JavaScript, most I/O operations are provided through asynchronous, or nonblocking APIs. Instead of blocking a thread on a result, the programmer provides a callback (see Item 19) for the system to invoke once the input arrives:

downloadAsync("http://example.com/file.txt", function(text) {

console.log(text);

});

Rather than blocking on the network, this API initiates the download process and then immediately returns after storing the callback in an internal registry. At some point later, when the download has completed, the system calls the registered callback, passing it the text of the downloaded file as its argument.

Now, the system does not just jump right in and call the callback the instant the download completes. JavaScript is sometimes described as providing a run-to-completion guarantee: Any user code that is currently running in a shared context, such as a single web page in a browser, or a single running instance of a web server, is allowed to finish executing before the next event handler is invoked. In effect, the system maintains an internal queue of events as they occur, and invokes any registered callbacks one at a time.

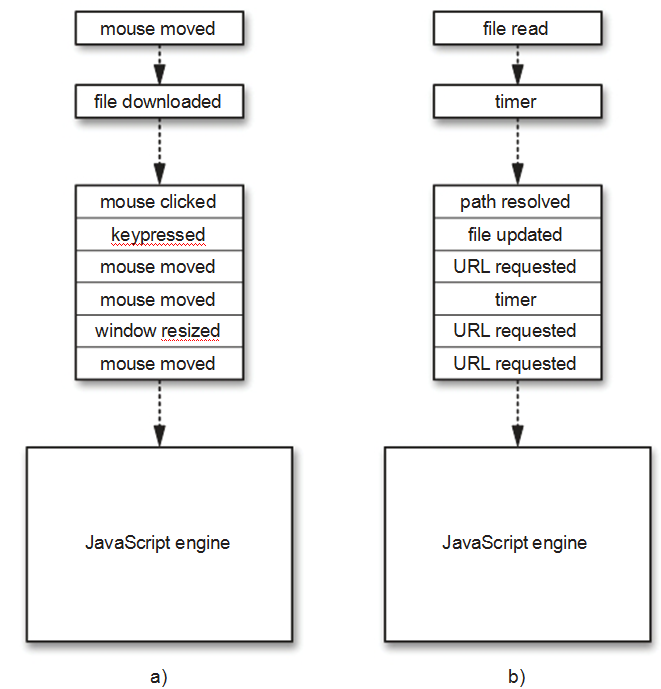

Figure 7.1 shows an illustration of example event queues in client-side

and server-side applications. As events occur, they are added to the

end of the application’s event queue (at the top of the diagram). The

JavaScript system executes the application with an internal event

loop, which plucks events off of the bottom of the queue—that is, in the

order in which they were received—and calls any registered Java Script

event handlers (callbacks like the one passed to downloadAsync above)

one at a time, passing the event data as arguments to the handlers.

Figure 7.1 Example event queues in a) a web client application and

b) a web server

The benefit of the run-to-completion guarantee is that when your code runs, you know that you have complete control over the application state: You never have to worry that some variable or object property will change out from under you due to concurrently executing code. This has the pleasant result that concurrent programming in JavaScript tends to be much easier than working with threads and locks in languages such as C++, Java, or C#.

Conversely, the drawback of run-to-completion is that any and all

code you write effectively holds up the rest of the application from

proceeding. In interactive applications like the browser, a blocked

event handler prevents any other user input from being handled and

can even prevent the rendering of a page, leading to an unresponsive

user experience. In a server setting, a blocked handler can prevent

other network requests from being handled, leading to an unrespon-

sive server.

The single most important rule of concurrent JavaScript is never to

use any blocking I/O APIs in the middle of an application’s event

queue. In the browser, hardly any blocking APIs are even available,

although a few have sadly leaked into the platform over the years.

The XMLHttpRequest library, which provides network I/O similar to the

downloadAsync function above, has a synchronous version that is con-

sidered bad form. Synchronous I/O has disastrous consequences for

the interactivity of a web application, preventing the user from inter-

acting with a page until the I/O operation completes.

By contrast, asynchronous APIs are safe for use in an event-based set-

ting, because they force your application logic to continue processing

in a separate “turn” of the event loop. In the examples above, imagine

that it takes a couple of seconds to download the URL. In that time,

an enormous number of other events may occur. In the synchronous

implementation, those events would pile up in the event queue, but

the event loop would be stuck waiting for the JavaScript code to finish

executing, preventing the processing of any other events. But in the

asynchronous version, the JavaScript code registers an event handler

and returns immediately, allowing other event handlers to process

intervening events before the download completes.

In settings where the main application’s event queue is unaffected,

blocking operations are less problematic. For example, the web plat-

form provides the Worker API, which makes it possible to spawn

concurrent computations. Unlike conventional threads, workers

are executed in a completely isolated state, with no access to the

global scope or web page contents of the application’s main thread,

so they cannot interfere with the execution of code running in from the main event queue. In a worker, using the synchronous variant of XMLHttpRequest is less problematic; blocking on a download does prevent the Worker from continuing, but it does not prevent the page from rendering or the event queue from responding to events. In a server setting, blocking APIs are unproblematic during startup, that is, before the server begins responding to incoming requests. But when servicing requests, blocking APIs are every bit as catastrophic as in the event queue of the browser.

Things to Remember

✦ Asynchronous APIs take callbacks to defer processing of expensive operations and avoid blocking the main application.

✦ JavaScript accepts events concurrently but processes event handlers sequentially using an event queue.

✦ Never use blocking I/O in an application’s event queue.

文章来源于:Effective+Javascript编写高质量JavaScript代码的68个有效方法 英文版